The background on the legal issues behind the 1919 World Series scandal is covered in part one of this series, which focuses on third baseman Buck Weaver. The subject of this article is the team's left fielder and best hitter, Joseph Jefferson Jackson, possessor of one of baseball's most colorful nicknames, "Shoeless Joe." It was a Greenville, South Carolina sportswriter named Scoop Latimer who hung that tag on Joe, based on an incident in his first year of organized ball. Jackson hated the moniker, which made him seem like a barefoot yokel, but it endured and remains eminently recognizable even to people who know nothing of baseball.

The man

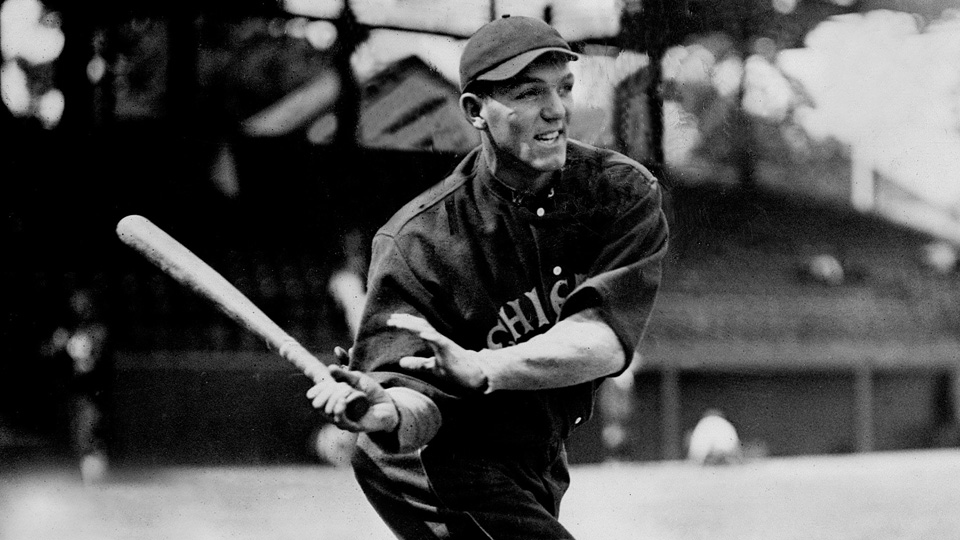

If you believe that Joe Jackson was a brilliant baseball talent, you are in good company. Such undeniable contemporary authorities as Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker claimed that Joe was the greatest natural hitter in the game. The peerless Babe Ruth said, "I copied (Shoeless Joe) Jackson's style because I thought he was the greatest hitter I had ever seen." The video to the right shows how Joe's lunging, all-out swing was incorporated into the Babe's own style. Shoeless Joe also had the most powerful throwing arm of his day. In one major league charity exhibition, he easily won the throwing contest with a heave of nearly 400 feet. (The trophy he won is shown below.)

On the other hand, if you believe that success came to him effortlessly, you are better off not knowing about his two partial seasons playing for the Philadelphia Athletics. The big club called Jackson up in 1908, when he punished American League pitching for a mighty .130 average, and then again in 1909 when he raised the bar to .176. For the two years combined, he batted .150 with no extra base hits and a single walk, for an OPS of .321. That translates to an OPS+ of only 1, on a scale in which 100 is an average player.

Joe had the talent even then, but he was full of self-doubt. A country boy from a rural mill town in South Carolina, he was totally intimidated by the size of Philadelphia and the rude treatment he received at the hands of his teammates, northerners who ridiculed him for his lack of education, his uncouth manners, his suspicious nature, and his offbeat superstitions. (He once had an astounding day after a young girl gave him a hairpin, so he would never again take the field without a woman's hairpin in his hip pocket.) A typical group of ballplayers around the turn of the 20th century would never be confused with the Algonquin Round Table to begin with, but even by their minimal standards of sophistication, Joe was a rube. According to most sources, he had started working in the local textile mill when he was six or seven and never went to school at all. SABR's Black Sox committee reported (December 2012 newsletter, page nine) that Joe claimed in the 1940 census to have a third grade education, but if he lasted that long, he wasn't destined to be valedictorian because the adult Joe could neither read nor write.

After the first game he played in Philly, he lasted only a few days in town before getting on a train back to South Carolina on the pretext of tending to a sick uncle. The team dragged him back soon enough, but he left again after a frustrating 0-for-9 double-header in September, this time without permission, and was then suspended from the team. Contrary to a newspaper headline which claimed he would never play organized ball again after that suspension, Joe was back with the club again in spring training, although he never did adjust to life in Philadelphia, and he never did fit in with his teammates. He did admire manager Connie Mack, but Mack liked intelligent ballplayers, so it was probably inevitable that a man called the Tall Tactician would eventually give up on a bumpkin called Shoeless Joe. In a rare strategic misstep, Mack lost one of the best three-season performances in the history of the game when he sold Joe to the Cleveland Naps. Joe assimilated more easily with his new peers, among whom were many other players from the South, and his improved comfort level allowed his brilliant baseball talent to shine through. In his first three full seasons in Cleveland, Shoeless Joe hit the baseball as well as anyone ever has. The great Ty Cobb was then at the peak of his abilities, and a comparison of their performances from 1911 to 1913 indicates that Joe was approximately as good as Cobb.

| HITS | 2B | 3B | HR | BB | SB | K | BA | OBP | SLG | OPS | |

| Jackson | 656 | 128 | 62 | 17 | 190 | 102 | 88 | .393 | .462 | .574 | 1.036 |

| Cobb | 641 | 95 | 63 | 19 | 145 | 195 | 104 | .408 | .463 | .585 | 1.048 |

The only strong argument to prefer Cobb in that comparison is that he was a far better base stealer, and that was at least somewhat offset by the fact that Joe walked more, struck out less, and hit more doubles. That's how good Joe was then: about as good as Cobb at his best. Competing directly against his legendary teammate Nap Lajoie (who was so good the team was named after him) and other future Hall of Famers like Cobb, Tris Speaker, Eddie Collins and Home Run Baker, Joe led the American League in hits in two of those three years, and led at various times in doubles, triples, on-base percentage, slugging average, and OPS. He is probably the once and future possessor of the record for the best batting average by an official rookie, because his astonishing .408 mark is not likely to be matched. Among players with 500 or more plate appearances, no subsequent rookie has come within fifty points of that mark.

Because contemporary pop culture has apotheosized Shoeless Joe, it is not generally remarked that Joe was never really as good again as he was in that initial period, at least not until the introduction of the "lively ball era" in 1920. In those first three full seasons he was really as good as his legend, but in the subsequent five years, playing for Cleveland, then Chicago, he was plagued with problems. He injured his knee severely in an auto accident on July 7, 1915 and was out of the line-up for the next three weeks. He batted only .297 for Cleveland after the accident. Fearing a steep decline in his performance, and thus his monetary value, the club decided to sell him to Chicago that same summer, while his asset value was still high. He played the remainder of the 1915 season for the White Sox, but batted only .272 with his new club. His knee recovered in the off-season and his performance improved significantly the next year, but 1917 proved to be another disappointing season. The White Sox won the pennant that year, but Joe was hitting poorly because of an ankle injury sustained during spring training. His batting average dipped to .261 on August 11th. A late-season surge lifted him to .301, but he finished the season with only 13 stolen bases and 75 RBI. 1918 proved to be an even more miserable year, as he missed nearly the entire baseball season because of World War I. By the end of the five-year period from 1914 to 1918, Joe's lifetime average had dropped 40 points from its high water mark. He was still one of the game's strongest offensive forces, but he had dropped to a level achievable by mere mortals.

In the uniform muddied at the knees

With the shadows of a century now behind him

Isn't who you think it is.

For Shoeless Joe is gone, long gone

With a long yellow grassblade between his teeth

And a lucky hairpin in his hip pocket.

Nelson Algren ... Ballet for Opening Day (slightly paraphrased)

The scandal

The answers to three questions determine the relative guilt or innocence of each of the Black Sox.

- Did he conspire to commit a criminal act?

- Did he conspire to throw the World Series?

- Did he actually do anything to throw the Series?

The answer to the first question about criminal conspiracy is a resounding "no" for all of them, including Joe. Even if every accusation against them had been true, they were not guilty of a crime, based on the judge's instructions to the jury in the Black Sox criminal trial.

"The State must prove that it was the intent of the ballplayers and the gamblers charged with conspiracy to defraud the public and others, and not merely to throw games."

Throwing the World Series was not a crime in 1919, and neither therefore was conspiring to do so. Legally, the players were simply getting paid to lose baseball games, just as Comiskey had paid them to win. In agreeing to do so, they may have failed to honor their contracts with Comiskey, but contractual disputes are a matter for the civil, not criminal courts. The players were brought to trial on contrived charges which were virtually impossible to prove beyond a reasonable doubt. There was no convincing evidence that they intended to defraud bettors, their boss Charles Comiskey, or their guileless teammates. In fact, the prosecution made no mention of "conspiracy to defraud" at any time during their case, thus making the jury's decision a simple and obvious matter.

Writing in the February 1, 1988 edition of the American Bar Association Journal, James Kirby concluded (page 68):

"If the intent to throw games plus taking money plus agreeing to lose and actually losing were not enough, the prosecution never had a chance. The law was simply inadequate for the Black Sox' offenses, even if the worst about them is believed."A somewhat more detailed overview of the legal niceties may be found in Part I of this series. A truly detailed and painstakingly assembled overview is presented in "Black Sox in the Courtroom" by William F. Lamb, a former prosecutor whose 2013 book is must reading for anyone interested in the legal aspects of the Black Sox scandal.

The answer to the question about whether Joe deliberately gave less than his best effort on the field is indeterminate. Modern pop culture mythology has exonerated Jackson, but the evidence is not that clear, especially when it involves his defensive play. Much of the modern perception of Joe's innocence is expressed in oft-repeated phrases based on his sympathetic portrayals in works of fiction, and the fact that Joe himself contributed as much as anyone to his own legend-building. In a 1949 interview, he said:

"I handled thirty balls in the outfield and never made an error or allowed a man to take an extra base. I threw out five men at home and could have had three others, if bad cutoffs hadn't been made."

Joe apparently had himself confused with Superman. He actually had sixteen put-outs, threw out one batter at home, allowed at least one runner to take an extra base on him (Morrie Rath in game one), and dropped a fly ball. He was not charged with an error in the World Series only because the official scorer was generous. When Jackson dropped a ball in game eight, the scorer gave Edd Roush a double on the hit off Joe's glove. Joe also made a suspicious play in game four. Baseball superstar Tris Speaker, generally considered the best defensive outfielder in history before Willie Mays come along, covered the 1919 World Series as a writer for the Cleveland Plain Dealer and questioned Jackson's shallow positioning that allowed Greasy Neale's fly ball in the fifth inning of that game to sail over his head for a double. Speaker's fellow Cleveland correspondent, sportswriter Harry Edwards, was not so gentle in his criticism. In the October 5th, 1919 edition of the Plain Dealer, he said that "Jackson played Neale’s fly to left like an old lady." (A summary of the Speaker and Edwards comments is in the SABR Black Sox Scandal Newsletter, June, 2015 edition, pages 3-6.)

Other analysts have found even more of Joe's plays suspicious. Dan Holmes of the Wahoo Sam baseball blog contends:

"In the fourth inning of Game One, Jackson fielded a ball hit to the base of the wall in left-center field. The ball was played into a triple, in part due to his casual fielding. Two runs scored. The next batter hit a ball to left field for a hit, which Jackson gathered and threw late to the infield, allowing the runner (Morrie Rath) to reach second. Eddie Collins later testified that he found the play puzzling because Jackson rarely made such mistakes. The following batter singled, scoring Rath."

One may not assume that there was any dishonesty involved in any of the plays cited above. Even the greatest players drop balls and make bad throws. They do so far less often than you or I would, but they do so, even in critical moments, because there is no such thing as baseball perfection. Willie Mays made more than a hundred errors in his career, as did Joe DiMaggio, Tris Speaker and Shoeless Joe Jackson himself. But if Joe Jackson's fielding in the 1919 World Series provides no definitive evidence of malfeasance, neither can it exonerate him, as Joe and many others have claimed.

Nor is it possible to assume that Joe's exaggerated description of his play, as recalled three decades after the fact, is evidence of a cover-up. As an illiterate man in an age before television, Joe could rely only on his memory to reconstruct the past. He may have repressed the memories he regretted, thus genuinely believing his preferred version of those events. Even those of us with access to written or recorded evidence sometimes do that.

As far as Joe's batting performance in the World Series goes, his apologists note that Joe batted .375 in the 1919 World Series. That fact alone provides no evidence that he did his best at the plate. To claim so is to ignore the oft-misleading impact of small sample sizes. In comparison to the eight games of the World Series, consider his first eight games of the regular season. He went 17-for-34. That means he could have intentionally struck out in four of those 17 at bats when he actually got hits, and the resulting 13-for-34 would still have left him with a .382 batting average, even at that high level of cheating! Or consider the first 14 games of July, when he went an unearthly 29-for-56. He could have tanked eight of the at bats when he actually got hits, and his batting average for that period would still have been .375. Because his great ability gave him the opportunity to hit .500 or better in a sample size of 8 or even 14 games, his .375 average in the Series does not prove that he was doing his best. Nor does it prove that he slacked off. Given the small sample size of eight games, that performance proves nothing.

One may argue quite fairly that Joe performed far below his abilities at the crucial moments in the Series. It's not clear whether the Sox were playing to win in the last three games, but they were almost certainly trying to lose the first five. They did lose the four started by conspirators Cicotte and Williams, and Jackson himself told the Chicago press that they tried to lose the other one, but failed because Dickey Kerr stubbornly refused to allow a run!

Joe came to bat six times with runners in scoring position in those five games.

- Game one: Sixth inning. One out. Collins on second, Weaver on first. Joe grounded out to first base. Felsch closed out the inning with a weak fly ball.

- Game two: Sixth inning. One out. Buck Weaver on second with a double. Joe struck out looking. Felsch then closed out the inning with a fly ball.

- Game three: Third inning. None out. Collins on second, Weaver on first. Joe popped up a bunt. This could easily have been a double or even a triple play with the runners going, but they got back in time. Although Joe only delivered one out, Felsch proved up to the task of killing the rally by grounding into a double play. Also worthy of mention was the sixth inning in game three, when Jackson and Felsch again worked their magic. Jackson singled to lead off the inning, then was promptly caught stealing, whereupon Felsch walked and was also out stealing! On base percentage: 1.000. Base runners: none. Joe apparently wasn't kidding when he said they tried to throw this game!

- Game four: Third inning. Two out. Collins on second. Joe hit what should have been the inning-ending grounder to second, but Morrie Rath inconveniently bobbled it, leaving runners on first and third, and putting pressure on Happy Felsch to deliver the third out, which he promptly did with a grounder of his own.

- Game five: First inning. One out. Leibold on third, Weaver on first. With just a single out, it was difficult for Joe to avoid batting in a run this time. After Joe had struck out in games two and four, another K would have raised a lot of eyebrows, and putting wood on the ball was risky because Leibold might have scored on a grounder, a bunt, or a fly ball. Amazingly, Joe pulled off the one form of contact that couldn't possibly score a run: he hit an infield pop-up. That provided the second out, thus allowing Felsch many options to deliver the third out without causing a run to score.

- Game five again: Ninth inning. Two out. Weaver on third with a triple. With two outs, Joe needed no help from Felsch this time. He grounded out to end the game.

There was another suspicious oddity in Joe's performance during those five games. In the space of nine plate appearances from game two to game four, Joe struck out twice. That may not seem suspicious to you if you follow the world of 21st century baseball, but 1919 was part of a very different era, one in which strike outs were rare in general, and were especially rare when Joe was at the plate. He was the very best in the game at avoiding them. Of all the hitters in baseball who qualified for the 1919 leadership in rate stats, Joe struck out the fewest times, as well as the least frequently. During the regular season he struck out only ten times in 599 trips to the plate. That represents a probability per at bat of .0167. Given that probability of an event occurring, the likelihood that such an event will occur twice or more in nine occasions is less than 1%. The odds were about 100-1 against that being a sample of Joe's honest play. It is not possible to calculate the specific odds against Joe taking a called third strike with a runner in scoring position, as he did in game two, because the 1919 data are insufficient to create that calculation. At the current level of knowledge, it is not known how often he took a called third strike in any situation, but I'm guessing that a bookie not "in the know" about the fix would have given you close to 100-to-1 odds if you had wanted to bet on a called third strike before Joe stepped in, given that the odds established by the season were 59-1 against any strikeout at all!

The situational statistics cannot establish anything more than deep suspicion. Joe's own words, however, do serve to convict him of sub-par play. In chambers, before testifying to the grand jury, Jackson told Judge McDonald that "he had played hard, but that he could have played harder." That judge testified to this under oath at the subsequent criminal trial. (New York Times, July 26, 1921.) In elaborating on the same conversation during his testimony at Jackson's back-pay suit in 1924, Judge McDonald testified that Jackson said "he had made no misplays that could be noticed by the ordinary person, but that he did not play his best." On the day of his grand jury appearance, he had a few drinks, talked to the judge in chambers, gave his grand jury testimony, then had many more drinks with the court's bailiffs. By that evening, Joe's tongue was far too loose when he talked to the Chicago press, including the Chicago Tribune. He not only repeated many of the details he had told the grand jury, but he added:

"And I'm giving you a tip. A lot of these sporting writers that have been roasting me have been talking about the third game of the World's Series being square. Let me tell you something. The eight of us did our best to kick it and little Dick Kerr won the game by his pitching. Because he won it, these gamblers double crossed us for double crossing them." (Emphasis mine)

The remaining key question involves whether Joe was part of the conspiracy to throw the World Series. The answer is an unequivocal "yes." Whether or not he played his best, his part in the conspiracy is established by his own testimony to the grand jury. If throwing the World Series had been a crime at the time, he would most certainly have been guilty of conspiring to do so.

Here's what he admitted in his testimony:

- His teammate Chick Gandil offered him ten thousand dollars to help throw the World Series, and he refused - until Gandil upped the offer to $20,000, at which point he agreed. The amount was to be paid in installments after each game.

- After game one of the series, not having seen a penny of the promised money, he asked Gandil, "What is the trouble?"

- Then, after "we went ahead and threw the second game, we went after him (Gandil) again."

- After the third game, still having received no cash, he told Gandil “Somebody is getting a nice little jazz, everybody is crossed.” Gandil told him that the gamblers had double-crossed the players.

- Finally, before the return trip to Cincinnati for game six, teammate/roommate Lefty Williams handed Joe an envelope containing five thousand dollars. Jackson had expected more by this time, so he asked Lefty "what the hell had come off here," and was again told they had been double crossed. Jackson could only speculate whether he had been cheated by the gamblers, by Chick Gandil, or even by his friend Lefty Williams. He suspected any or all of them.

Joe later changed his story, making himself seem innocent, thus hoping to bolster his claim for back pay in a civil suit that was tried in Milwaukee in 1924. Jackson delivered the second version of his participation when he had been deposed on April 9, 1923, as reported on April 23rd in a syndicated column by Frank Menke. In that version, he knew nothing at all of the fix until two or three days after the Series ended, when Lefty Williams threw $5,000 at his feet and told him that the player-conspirators had convinced the gamblers that they could pull off a fix by assuring them that Joe was in on it. Hearing this, an outraged and "dumbfounded" Jackson supposedly went to Comiskey's office the very next day to tell him what had happened - and was rebuffed by Comiskey's secretary. This story made no sense since Williams could not have seen Joe two or three days after the Series finished. Joe and his wife had left for Savannah on the evening after the final game. The story was not only logistically impossible, but it contradicted Jackson's previous account, the accounts of his teammates, and even the account of Jackson's own wife!

His story changed again during the civil court proceedings. It appears that somebody had informed him that the account in his deposition was logistically impossible, so he tightened the time line in the third version of the story. This time he asserted that Williams handed him the money after the final game of the series and he visited Comiskey the next day, thus allowing his story to reconcile with the timing of his train trip to Savannah.

Jackson testified to the new story under oath in his civil suit, which gave him a sticky perjury problem, since he had previously told two different, contradictory stories under oath in the grand jury proceedings and the deposition. The time-line problem could have been explained away by a memory lapse, but the grand jury testimony was another matter. Given the discrepancies between his testimony in the civil suit and his testimony before the grand jury, he logically had to have perjured himself one time or the other. Joe chose a bizarre strategy to work his way out of this dilemma. When he was cross-examined about the contents of his grand jury testimony in 1920, he did not attempt to blame coercion or a faulty memory. In fact, he made no attempt to reconcile the differences between his two versions of the narrative. He simply denied saying everything he had said to the grand jury, offering statements like, "I didn't make that answer." When confronted with the particulars of his testimony, he denied everything line-by-line, more than a hundred times under oath. He seemed to be unaware that the court record consisted of more than just some typed pages. The judge, the court stenographers and the grand jurors were all still alive and available to verify that the transcript was an accurate account of what Joe had actually said. Some of them were called to provide that testimony, thus leaving Joe with more that a hundred instances of perjury which could be proved beyond a reasonable doubt. In fact, beyond any doubt.

The excerpt below comes from "Black Sox in the Courtroom" by William F. Lamb:

The presiding judge became so frustrated with the entire proceeding that he sent the jury out of the room and had Joe thrown into a jail cell, arrested for perjury in his own back-pay suit!

There was one time when Joe called Commissioner Landis to ask for a chance to explain his position. Landis told sportswriter Frank O'Neill: "Jackson phoned and asked whether I would give him a fair hearing. I said I give every man a fair hearing. Jackson said, 'Thanks, Judge. Do you know that those gamblers never paid all they owed me?'" (Rothstein, David Petrusza, p. 366) The hearing ended there.

After the scandal:

Joe was banned from organized baseball after the criminal trial, but continued to play ball for many years in textile league, sandlot and semi-pro contests. He played for the Greenville Spinners in 1932, more than a decade after his banishment from the big show. There he still hit the ball hard and regaled the locals with stories of the old days, including the origin of his legendary dark bat. Although aging and gray, Joe still appeared to be in playing condition, and was still wielding Black Betsy, as pictured here.

When he wasn't playing ball or coaching the local kids, he and his wife ran a successful dry cleaning business in Savannah, then a liquor store in Greenville, South Carolina. By all accounts, he could still hit the ball authoritatively for the Woodside Mill team until he was fifty, even as his fielding declined under the weight of some seventy additional pounds. He told The Sporting News in 1942 (cover story, story continued) that his weight had climbed as high as 254 pounds, compared to 170 at the start of his career in the minors, and a major league playing weight of 186. The images below show him at the beginning and end of his adult playing days.

The extra weight contributed to health problems and Joe had several minor heart attacks over the years. The fatal one came on December 5, 1951 in Greenville, where his obituary mentioned that he was widely loved in the community.

Shoeless Joe Jackson did not instigate or design the World Series fix with the gamblers. Two of his teammates, Cicotte and Gandil, did that. He did not attend the strategy meetings, meet with the gamblers, or join the inner circle like Gandil's henchmen, Risberg and McMullin. He didn't stumble his way through the World Series like Risberg, who batted .080 and made four errors, or Lefty Williams, who became (and remains) the only man to lose three starts in a single World Series by posting a 6.61 ERA, a preposterous figure in the deadball era.

Shoeless Joe was roped into the conspiracy by Gandil. Before his grand jury testimony, he was hoodwinked out of his right to a lawyer by Alfred Austrian (Comiskey's lawyer). He was almost certainly tricked into thinking he was testifying before the grand jury with immunity from prosecution. He was probably not smart enough to know that his lies under oath represented to society a very different level of deception from simply telling a few old war stories and fish tales. He became beloved in South Carolina, and was worshipped by the local kids, for whom Joe always found time.

Those are all mitigating circumstances, but make no mistake about it: he was corrupt. He agreed to take the money and then he kept asking where it was. He originally tried to make amends on grand jury day by telling the truth, but he changed his mind after that day and started lying about it. He lied under oath more than a hundred times at his civil trial, and then he continued to tell the same lies all of his life. In 1941, in reference to his grand jury testimony, he told Shirley Povich of the Washington Post, "There never was any confession by me. That was trumped up by the court lawyers." As time went on, the lies became bigger, until he was finally presenting himself as the man who gallantly threw out five runners at the plate while totally unaware of any skullduggery until after the World Series had ended, at which point he marched into Comiskey's lair and insisted on cleaning up the mess.

Should we forget what he did, and all the lies he told about it, because he was a great player who wasn't smart enough to know any better? I don't buy it. I don't buy it for Pete Rose, and I don't buy it for Joe Jackson.

Should he be in the Hall of Fame? I don't know. I can't answer that unless you tell me what the Hall of Fame is for. If it exists only to enshrine the game's greatest performances on the field, then Shoeless Joe absolutely belongs there. The adjusted OPS+ for his career is the seventh highest in history. From 1911 to 1913 he was as good as anyone ever was. The man hit .408 as a rookie, for heaven's sake.

On the other hand, if the Hall exists to enshrine those who played well and honorably, who graced America's ballfields and left the game better in their wake, then I would not vote to include a man who agreed to take money to throw a World Series. I know there are other scoundrels already in the Hall, but that is an unpersuasive argument to add one more. If I am asked to cast a vote for Fictional Shoeless Joe, that sympathetic, thoughtful, right-handed batter played by Ray Liotta in Field of Dreams, I'm all in, but the real man on the right leaves a sour taste in my mouth.

Next, in part III: Arnold Rothstein