A tale of two cities parks in one city

The last couple of decades have brought about a revolution in baseball statistics. Analysts like Bill James have given us new ways to view the raw data, while tireless researchers keep giving us ever more raw data to view.

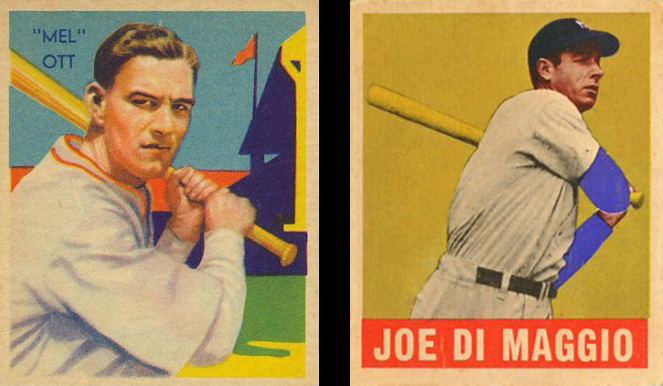

One thing that we have now that we did not have before is detailed home/road and park data. While not every stat has been broken down into home and away segments for baseball games from the deadball era and the 19th century, we have solid numbers for every season since 1920, and we have home run data dating back even before that time. This information sheds new light on some of our previous assumptions. When I was a boy, we saw these lifetime home run totals: Mel Ott 511 (then the all-time NL leader), Joe DiMaggio 361. We could see that Ott had far more at-bats, but there was a gap of 150 homers between them. The numbers seemed so decisive, right?

Wrong.

Ott was a left-handed hitter who played his entire career in the Polo Grounds, where the right field foul pole was about 250 feet away.

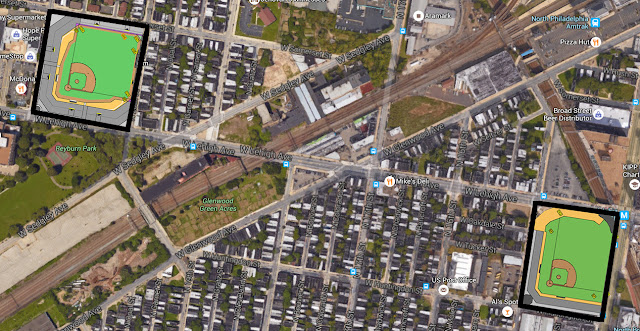

DiMaggio played his entire career just across the river in Yankee Stadium. Yes, they were that close. See below.

Here is how they were oriented, relative to the modern street grid, with North on top. The original Yankee Stadium, DiMaggio's haunt, is the one on the lower right. Just above it is the newer one.

The Bronx park was much friendlier to lefties than to the right-handed DiMaggio. That produced some freakish home/road splits in their home run stats.

Home

|

Away

|

|

Ott

|

323

|

188

|

DiMaggio

|

148

|

213

|

Relative to each other's stats, their home parks made a difference of about 200 homers. If they had played their careers in neutral parks, assuming 2X their road numbers, DiMaggio would have finished with 50 more homers than Ott rather than 150 fewer!

On a "per at-bat" basis, the difference is far more dramatic. DiMaggio hit a homer every 16 at bats on the road, while Ott connected every 26 trips. Over a hypothetical season of 550 at-bats, that would result in 34 homers for DiMaggio, 21 for Ott. DiMaggio was not only a better home run hitter than Ott, he was far better, beyond any shadow of doubt. If Mel Ott had neutral home/road stats, he would have finished with some 370 homers, about the same as Tony Perez or Gil Hodges. That means he was a good power hitter, but certainly not as good as we thought he was fifty years ago.

And it could have gone much worse for him than "neutral." In his career splits, we see that he had 268 at-bats at Shibe Park and never hit a single homer, while batting .220. In Cincinnati he hit only thirteen homers in 699 at-bats.

This section makes it seem that I am disparaging Mel Ott, and that would be misleading. It's important to realize that while the Polo Grounds inflated his home run totals, Ott was an excellent hitter whose lifetime batting average was actually better on the road! In fact, he had more extra base hits on the road! His lifetime splits clearly indicate that the Polo Grounds basically just converted his doubles and triples to homers.

Enough about Ott, already.

Who else benefited greatly from home parks?

To begin with, the lifetime totals are wildly and positively skewed for any lefty hitter who played in that rickety old wooden stadium known as the Baker Bowl or anyone who played in Coors Field.

Chuck Klein rode the Baker Bowl to the Hall of Fame. His lifetime batting average there was a phenomenal .395 with a .705 slugging average.

Throughout Klein's career, he hit 192 homers at home, only 108 on the road. The following representation of the Baker Bowl will show you why.

The Baker Bowl also affected Klein's fielding stats. He not only hit the ball toward the short right field fence, but he was also a right fielder. Once he learned how to play the wall and the tiny area available to him, he was able to use his strong arm to throw out a record number of runners who just didn't realize how fast he could retrieve the ball and how close he was to the infield. One year he amassed 44 outfield assists, a modern record which will probably never be approached, given that the highest total since World War II has been Roberto Clemente's 27 in 1961.

Cy Williams, another lefty who played most of his career in the Baker Bowl, didn't make it into the Hall of Fame, but he won four home run crowns and the friendly Bowl was a major contributor to three of them. In 1920 he led the National League with 15 homers, 12 of them in the Bowl. By 1923, the National League had started to produce similar power numbers to the AL, and Williams blasted 26 homers at home. Throughout his career, he hit 167 dingers at home, just 84 on the road. Among all major leaguers with 250 or more homers, he has the highest percentage of his total at home (66%); Chuck Klein has the second-highest (64%). Both were lefties who played their home games primarily at the Baker Bowl.

It's time for one of my famous barely-related digressions. You saw above how close Yankee Stadium was to the Polo Grounds. Just to save me another essay ("Major League Neighbors"), here's an aerial of the Baker Bowl (background) and Shibe Park (foreground), which were used simultaneously for about three decades (1909-1938), and were only a few blocks apart on Lehigh Avenue.

Damn, those old ballparks always look so depressing in black and white. I have to think that doesn't convey the feeling of what it was like to pass a day at the park. Here's what they looked like when they were young and fresh.

Here's how the parks were aligned, relative to a Google Maps image of the neighborhood today, You can enlarge the image by clicking on it.

Enough of the digressions. If you love those old parks as much as I do, there is a site called BallparksofBaseball.com which is just filled with images, data and stories about them (and the newer parks as well). Check it out. I especially enjoy looking at how the parks used to fit into the city grids, and how the same blocks look today, post-stadium. We now return to our regularly scheduled program.

Todd Helton played his entire career for the Rockies. He was the Chuck Klein of Coors Field. Over the course of his career, he batted .345 at Coors with 32 homers per 162 games and a .607 slugging average. On the road he batted .287 with 20 homers per 162 games and a .469 slugging average. Those three elements are almost identical to Chuck Klein's lifetime road performance (.286, 20, .466). He hit 227 homers in Coors, 142 on the road throughout his career.

Larry Walker's performance in Coors was even better than Helton's. He batted .381 there, with 41 homers per 162 games and a .710 slugging average. His comparable lifetime averages on the road were .278, 27, .495. Factoring out the effect of their home parks, Walker was a slightly better hitter than Klein or Helton. His lifetime home/road stats are not as dramatic as Helton's because he played in other home parks throughout his career, but overall he hit 215 homers at home, only 168 on the road.

Here are two other well established sluggers with dramatic home/road splits that worked in their favor.

Ron Santo: 216 at home, 126 on the road. Wrigley Field has been a tremendous hitter's park in some years, not so much in others, presumably based on the unpredictable wind direction and velocity in Chicago. Overall, it was very beneficial to Ron Santo's career. Santo received the most dramatic benefit from Wrigley Field, but his long-time teammates, Ernie Banks and Billy Williams, also loved the "friendly confines." Banks hit 290 homers at home, only 222 on the road. Williams hit 245 at home, 181 on the road. Wrigley probably added 50-100 homers to each of their careers. Those confines seem to be friendly to batters on both sides of the box. Santo and Banks batted right-handed, while Williams swung from the port side.

Hank Greenberg: 205 at home, 126 on the road. Greenberg absolutely owned that park in Detroit. In 1938 he hit 39 homers at home, a record which has never been broken. That's the same number Bonds hit at home when he poled 73 in 2001. McGwire hit 38 and 37 at home in his two big years. In 1937, Greenberg had 101 RBI at home, which seems eye-popping until you see the 1930 numbers for Hack Wilson, who drove in 116 runs at home that year. (That's not a typo.) Wilson's numbers are even more impressive when you consider that the man was not that much taller than Eddie Gaedel.

Which players were hurt by their home parks?

The three primary power hitters of the old Milwaukee Braves (Aaron, Adcock, Mathews) were hurt by County Stadium. All three of them are even more powerful than you think they are. I don't know the scientific explanation for it because the dimensions of the park were symmetrical and typical, and there was nothing very unusual about Milwaukee weather conditions, but the ball was just dead there, and that park really slowed down the home run hitters.

Henry Aaron's career home/road breakdown doesn't reflect it, because he was able to balance off the Milwaukee years with some great home park advantages in Atlanta, but Aaron was affected substantially by having played in County Stadium. You know that Aaron never hit 50 homers in a season, thereby denying him a special place in the baseball pantheon, but he had three separate years in Milwaukee when he hit at least 25 on the road. A road total like that normally guarantees 50 for the year, but Aaron finished with 44-45-44 those years. In his twelve years with the Braves in Milwaukee he hit 185 homers in County Stadium and 213 on the road (his ratio was 10:12 when he played for the Brewers, for a composite of 195-225 at Milwaukee County Stadium), but after the Braves left Wisconsin, Aaron hit 190 at home for them and 145 on the road, so his lifetime totals just about balanced out (385-370).

Ed Mathews wasn't so lucky. He played most of his career with the Milwaukee Braves, and thus finished with 238 at home, 274 on the road. In his biggest year (1953), he hit only 17 at home, but 30 on the road. In his second biggest year (1959), it was 20/26.

Big Joe Adcock seems to have been affected the most of the three. He hit 137 at home, 199 on the road. During his Milwaukee years in was 104/135.

Mathews was a lefty, the other two batted right-handed. The park seems to have played no favorites in that regard.

The relative impact of County Stadium vs. Wrigley Field really starts to appear immense when aggregated for several sluggers. The table below contrasts two famous slugging trios of the 50s through 70s: the Cubs (Banks, Williams, Santo) and the Braves (Aaron, Mathews, Adcock). The numbers are their lifetime home run totals

| Home |

Road |

|

| Cubs Trio |

751 |

529 |

| Braves Trio |

754 |

839 |

Finally there is the special case of Goose Goslin. Baseball writers and fans didn't know much about how to analyze stats back in the day, but even then they knew that the Goose was getting cooked by cavernous Griffith Stadium. It all became obvious in 1926 when Goslin hit 17 homers on the road - and zero, zilch, nada at Griffith. People started to realize that he wasn't a guy with mid-teen homer power, as he had always appeared to be, but a true power hitter capable of big numbers in the right environment. That proved to be more than theoretical when the Senators dealt him off to the St Louis Browns, and he proceeded to hit 37 homers for the year - even though he spent the first third of the season in Griffith Stadium, where he hit only three homers in 135 trips. That trade probably got the ol' Goose in the Hall of Fame. People had already known that he was an RBI machine, since he knocked in 90 or more runs thirteen times in his career, but he had never hit as many as twenty homers in any season before that one, and the fact that he finally put up a big homer number certified his credentials as a slugger. By the way, that's the same number of 90+ RBI seasons as the great Jimmy Foxx, even though the Goose could not muster even half as many homers as Double X. Goslin finished his career with more than 1600 RBI, more than Mike Schmidt, although he had only 248 homers. One wonders what kind of RBI numbers he might have accrued at the Baker Bowl. Over the course of their careers, Goose actually hit far more road homers (156) than Chuck Klein (108), but he hit only 92 at home, compared to 192 for Klein. Even that ostensibly extreme ratio has been moderated by the fact that he got to spend a few years out of Griffith Stadium in the second half of his career. In the 1920s, playing exclusively at Griffith, he averaged only three homers per year in his home park, amassing a mere 24 at home for the entire decade, as contrasted to 84 on the road.

No comments:

Post a Comment