In the HBO series Winning Time, the actor playing Pat Riley, the ultra-successful coach of the Los Angeles Lakers, walks around with his dad's fire-damaged bat. The implication is that Pat rescued the bat after his dad had tried to burn it. The dad in question was outfielder Leon (Lee) Riley, whose story was really emblematic of an era in American sports that no longer exists. From the 19th century until about the 1960s, it was possible to be a career minor league ballplayer, thrilling small-town fans with athletic heroics in the summer, while working anonymous, pedestrian jobs in the off-season. Lee Riley was such a man.

His career got off to a promising start at age 20, when he found himself in single-A ball in his first year as a professional, by-passing all the lower levels except for a very brief stint (23 games) in class D. In his first full season in the tough Western League, he tore it up at the plate, batting .370 with a plethora of extra base hits.

His career got off to a promising start at age 20, when he found himself in single-A ball in his first year as a professional, by-passing all the lower levels except for a very brief stint (23 games) in class D. In his first full season in the tough Western League, he tore it up at the plate, batting .370 with a plethora of extra base hits.

Riley understood his limitations, and he was willing to put in the time and effort to overcome them. It took longer than expected, but he worked and worked on his fielding until he earned a well-deserved promotion to the Rochester Red Wings, the top farm club of the St. Louis Cardinals, with his major league dream within his grasp.

And then he ran smack into the Peter Principle, which suggests that each person rises until he reaches his level of incompetence. For Lee Riley that level was the International League. He batted only .276 with no power at Rochester, in an age when just about every major league outfielder batted .300 or better against actual major league pitching. It was especially difficult to break into the St. Louis Cardinals' line-up. The 1930 St. Louis Cardinals were the highest-scoring NL team of the 20th century. They had 13 players with 100 at bats or more, and twelve of them batted in the .300s.

At that point in his career, Lee had had the bad fortune to get his two potential major league opportunities with the two teams that needed him the least! When Leon Riley went to Rochester, the hard-hitting Cardinals were the defending World Series champions, and it was soon obvious that Lee could not fit into their major league plans.

How did his performance drop so dramatically from class-A ball to AA? Lee himself said that it was because he couldn't hit lefties at that level. That formed the basis for one of Tommy Lasorda's best anecdotes, as recounted in the L.A. Times, July 13, 1988:

When Tom Lasorda was pitching for Schenectady of the Canadian-American League in 1948, the manager was Lee Riley, father of Laker Coach Pat Riley.

"We were playing Gloversville, and I’ve got ‘em beat, 2-1, and it’s in the top of the ninth inning. As I go out to pitch, Riley, who was coaching third, came to the mound, picked up the ball to hand it to me and he says to me, 'You’re in good shape. You’ve got three left-handed hitters in a row.’ And I was a left-handed pitcher, which meant things should be easy.

First left-hander doubles. Next left-hander triples. Next left-hander doubles. And now they’re winning, 3-2. And he comes to take me out, and as he starts to take the ball from my hand, he looks at me and he says, 'Know why I couldn’t hit in the major leagues?' I thought that was a very unusual question, but I said, 'No, Skip. No, why?' And he said, 'Because I couldn’t hit left-handed pitchers. But if you’d been there, I’d have been a star.'"

Whatever the explanation for Lee's failure, the fact remained that the Cards had sent him to the Rochester Red Wings with high hopes and much fanfare, but were so disappointed with him that they optioned him out even when it left the Rochester club desperately short of outfielders.

That's how his life went. He'd have a couple of good years, earn another promotion, then find himself back at a lower level than when he started. By the time 1938 rolled around, he was a 31-year-old veteran of 12 minor league seasons, but was in D ball with the 19 year olds, playing full-time while also acting as the team's manager.

His hot bat had granted him his fondest wish, yet another promotion to the International League as a player, this time with a Dodgers farm club in Baltimore. Unfortunately, that wish had unintended consequences, like the ones in the classic cautionary tale, "The Monkey's Paw." The fulfillment of that wish came with an ironic and crushing twist. Riley had stalled out his evolving managerial career for a pipe dream - the hope that he could now somehow hit International League pitching, despite the harsh lesson of his prior failure. The result was even more disappointing than his first trip through that league. In 38 games he batted .212 with one homer.

It was back to square one again.

By then he must have understood that a shot at the majors was only a dream, but baseball was his job and he was no quitter, so he accepted another demotion, and resolved to seek a managerial job in earnest. He soon found himself as a player/manager in a C league, where he had his best season to date, batting .391 with a league-leading 32 homers in the obscure Canadian-American League.

Given his track record, a solid performance at such a low level would not normally have led him back on a path to the majors, especially since his subsequent performance was disappointing, but fate intervened, in the form of Adolph Hitler. America needed able-bodied young men to fight in WW2, including young ballplayers. While many of the best and youngest major leaguers went to bat for Uncle Sam, the desperate major league teams were looking for bodies to fill out their depleted squads.

By 1944 and 1945, after years of war, roster spots had opened for all sorts of players who would not otherwise have been able to qualify for major league squads. There was a one-armed outfielder (Pete Gray, below center), a 15-year-old pitcher (Joe Nuxhall, below right), and a variety of older players who would otherwise have been retired, like Paul Waner, once a great star with the Pirates, hanging on in wartime as a grizzled Brooklyn Dodger (below left). In those segregated, pre-Robinson years, the Cincinnati Reds even snuck a black pitcher onto their roster, and nobody really paid attention.

The next year he found himself back in D ball yet again, playing against kids who could be his children, starting from the lowest player-manager level for the third time in his career, hoping once again to move up the managerial ladder. He was not a man who gave up easily, so he stubbornly lasted five more years in the low minors as a player/manager in the Phillies' farm system. As a player, he would never again reach as high as single-A, the level where he had played in his very first year, nearly a quarter of a century earlier.

When he finally stopped playing, he stayed in the Phillies' organization as a full-time minor league manager, and was awarded some promotions until he was finally back in class A, as manager of the Phillies' Eastern League teams in 1950 and 1951. The Phillies did a bit of manager-swapping in 1952, and Riley found himself managing the Wilmington Blue Rocks, who posed a respectable 72-66 record in the Interstate League. Unfortunately, the economics of baseball were changing. The Wilmington Blue Rocks went belly up, and the entire Interstate League collapsed. Facing a dwindling bottom line, the Phillies announced after the 1952 season that they were trimming their farm system from 12 teams to 9. Along with many others, Leon Riley lost his job that day, his baseball odyssey complete after 11 years as a manager, and a playing career that spanned 22 summers. He had accumulated more than 2,400 hits in pro baseball, including about 900 for extra bases, in the process of compiling a .314 lifetime average. At various times he had led minor leagues in doubles, triples, home runs, walks, RBI and batting average. He had once managed a team to a pennant. He had always done what was asked of him, having played D ball at age 20, then again at age 30, and finally at age 39. Despite his loyalty and hard work, he found himself unemployed at 46, with no non-baseball job skills. Feeling betrayed and abandoned, he went up to his attic and discarded all of his memorabilia dating back to the mid-20s, symbolically casting baseball out of his life, as documented by the eyewitness testimony of his son, the future Lakers coach.

And that brings us back to the scene described at the beginning of this article. As the story goes, Pat Riley rescued his dad's bat that day, preserved it, and treasured what it meant to his family's history.

---

Two of Leon Riley's children became professional athletes, albeit neither of them in baseball.

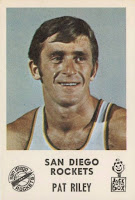

Pat Riley was a solid back-up player on one of the greatest basketball teams ever assembled, the 1971-72 Los Angeles Lakers, who finished the regular season 69-13 and breezed through the playoffs to the championship. Using their peak roster, if all players had been in their primes at the time, their starting five might have been the greatest ever assembled: Wilt Chamberlain, Elgin Baylor, Jerry West, Gail Goodrich and Happy Hairston. Pat Riley wasn't about to crack that line-up, but he was a dependable role player who carved out a 10-year career in the NBA.

I'm sure that you already know about his coaching career, which is one of the greatest in history.

Pat's much older brother, Lee Riley, chose football as his primary sport. He was a solid defensive back with a 7-year career in the NFL and AFL, and once led the league in interceptions. He was also used on special teams to return both punts and kickoffs.

After his pro career, he left the sports word and became a corporate vice-president.