Background: Nine Men Out

In 1921, eight of the Chicago White Sox and one player from the St. Louis Browns were permanently expelled from organized baseball for corrupt activities related to Chicago's defeat in the 1919 World Series. Two of the banned players, Buck Weaver of the Sox and Joe Gedeon of the Browns, had neither taken any bribes nor done anything directly to affect the results of any games, but were included in the baseball commissioner's housecleaning because they had found out what had been planned by various gamblers and the so-called Black Sox, but failed to come forward immediately to report what they knew.

At the time that Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis issued his decisions to ban the nine men, he was almost universally praised for taking bold and long-overdue action on baseball's gambling problem, which had been whitewashed for years, much to the dismay of many fans and baseball writers who were well aware of the cozy and inappropriate relationship which then existed between players and gamblers. As Chick Gandil, one of the accused players pointed out, decades after the scandal, "Where a baseball player would run a mile these days to avoid a gambler, we mixed freely. Players often bet. After the games, they would sit in lobbies and bars with gamblers, gabbing away." Landis ended that with strong, decisive action.

As time has passed, however, Landis's blanket ukase, which lumped all the Black Sox together in equal degrees of punishment, has been increasingly criticized because the players' behavior did not exhibit equal degrees of guilt. With some additional objectivity gained by a century of detachment from the outrage of the time, and having evolved a different sense of fairness, modern analysts are rankled by Landis's lack of subtlety in failing to distinguish between the corruptors and the corrupted, between those who wove the web of conspiracy and those merely trapped in it. Many modern fans also wonder how Landis could have banned the players at all, since they were found "not guilty" of all charges by a jury.

In particular, elements of modern pop culture have created a great deal of empathy for two of the Black Sox, third baseman Buck Weaver and the team's superstar, left fielder "Shoeless" Joe Jackson. Jackson was treated sympathetically in W.P. Kinsella's sentimental novel, "Shoeless Joe," and the movie made from it, "Field of Dreams," both of which forgave Joe his trespasses, such as they were. That story granted Jackson a second chance quite literally, and in so doing entreated its audience to grant one metaphorically. The most popular account of the Black Sox scandal, a putatively non-fictional book entitled "Eight Men Out," as well as its eponymous movie adaptation, made a strong case that Buck Weaver was unjustly punished, since his sentence was as harsh as the one imposed upon the players who organized the fix, took the bribes, and threw the games, although Weaver took no money and played firecely and unwaveringly to win. It is from the compelling narrative of that book and screenplay by Eliot Asinof (pronounced AY-zin-off) that most modern fans have formed their impression of the events and personalities that shaped the 1919 World Series fix.

But the established notions of popular culture are inevitably oversimplifications which lose the details and nuances of any situation, especially one as complex as this case, which is filled with unreliable narrators, contradictory accounts, widely accepted myths, evidence tampering, cover-ups, participants who changed their stories over time, and various mysteries which will probably remain unsolved because the keys to their solutions have been lost in a bubbling lather of passing time. Very little about the players' guilt can be established with certainty, but that does not free modern students from trying to come as close as possible to the objective truth.

In order to establish accurate gradations of culpability among the players, it's important to establish exactly what the Black Sox were accused of. There are three separate questions which should be evaluated for each individual player:

- Did he conspire to commit a criminal act?

- Did he conspire to throw the World Series?

- Did he actually do anything to throw the Series?

At a casual first glance, there seems to be no meaningful difference between #1 and #2, but separating them is no mere pettifoggery. It's an extremely critical distinction, because in 1919 there was no Illinois law specifically related to deliberate underperforming in a public sporting event. While the players who threw a game at that time might be in violation of tacit or explicit aspects of their contracts, that is not a matter for the criminal courts. The resolution of alleged contract violations belongs in civil litigation. In simplest terms, it was not a crime for them to throw the World Series. Since tanking the Series was not a criminal act, neither could it be a crime to conspire to do so, because conspiring to commit an act is only illegal if the act itself is illegal. It is illegal for your family to conspire to kill your rich Uncle Dwight, but it is certainly not illegal to conspire to throw him a surprise birthday party.

(Unless, I suppose, the surprise is designed to give him a fatal heart attack.)

We can begin with question #1, "Did he conspire to commit a criminal act?" because it is the easiest to answer in this case. The answer is a simple blanket assertion that applies to all nine men, based on the 1921 trial of the Black Sox: no. The prosecution's actual specific charges seem in retrospect to be (interpreted kindly) quixotic, or even (less kindly) desperate. Absent any spin, it's fair to say the charges have a contrived ring to them. The defendants were accused of conspiring to defraud some of the innocent White Sox of the difference between the winners' and losers' share of the World Series, for example, and they were originally accused of conspiring to defraud Charles K. Nims, an obscure gambler who had bet $250 on the Sox. The prosecutors wisely dropped the latter charge before the trial began. They did so for many reasons, not the least of which was that none of the Black Sox even had any idea who that man was, thus making it impossible for the prosecution to convince a jury that the players were conspiring to defraud him.

The defendants were found not guilty of all charges by the jury, based on the judge's explicit instructions, which were as follows:

"The State must prove that it was the intent of the ballplayers and the gamblers charged with conspiracy to defraud the public and others, and not merely to throw games."When the jury took only three hours to determine that the State had not proven that charge beyond a reasonable doubt, if at all, Judge Friend was all smiles, as reported by the Chicago Tribune on August 3, 1921.

On the other hand, many journalists of the day were shocked by the verdict, because several of the players had confessed their participation in the fix. Sportswriter H.G. Salsinger summed up the prevailing attitude in the August 11, 1921 edition of The Sporting News:

"There has never been a jury verdict that has aroused such wide discussion and so much unfavorable comment."

Subsequent reviews by legal experts, however, have confirmed that the jury technically had delivered the correct verdict based upon their instructions. Writing in the February 1, 1988 edition of the American Bar Association Journal, James Kirby concluded (page 68):

"If the intent to throw games plus taking money plus agreeing to lose and actually losing were not enough, the prosecution never had a chance. The law was simply inadequate for the Black Sox' offenses, even if the worst about them is believed."

In fact, when the prosecution had rested its case, Judge Friend granted defense motions to dismiss charges against two of the defendants and informed the prosecutors that he would probably set aside any jury findings against three others, including two of the players, since virtually no case had been presented against them. The technical legal issues involved in the case enable us to understand why the baseball commissioner felt he could expel all the Black Sox from baseball despite the "not guilty" verdict. The commissioner and the jury were ruling on two completely separate matters. The jury had to determine whether the accused had committed crimes. The commissioner had to determine whether the Black Sox had either conspired to throw or had actually thrown any ball games, acts which were not illegal at the time, but were obviously contrary to the best interests of both the general public and the institution of organized professional baseball. Although Commissioner Landis and the jury seem upon first impression to have come to opposite conclusions, this is illusory. Both may have been correct. The Black Sox were apparently not guilty of a crime, but nonetheless seem to have engineered a World Series defeat.

This brings us back around to Buck Weaver and Joe Jackson. If the Black Sox in general had conspired to throw and then had actually thrown the World Series, were those two men exceptions? Were they, at least, less guilty than the other defendants?

Buck Weaver

The player

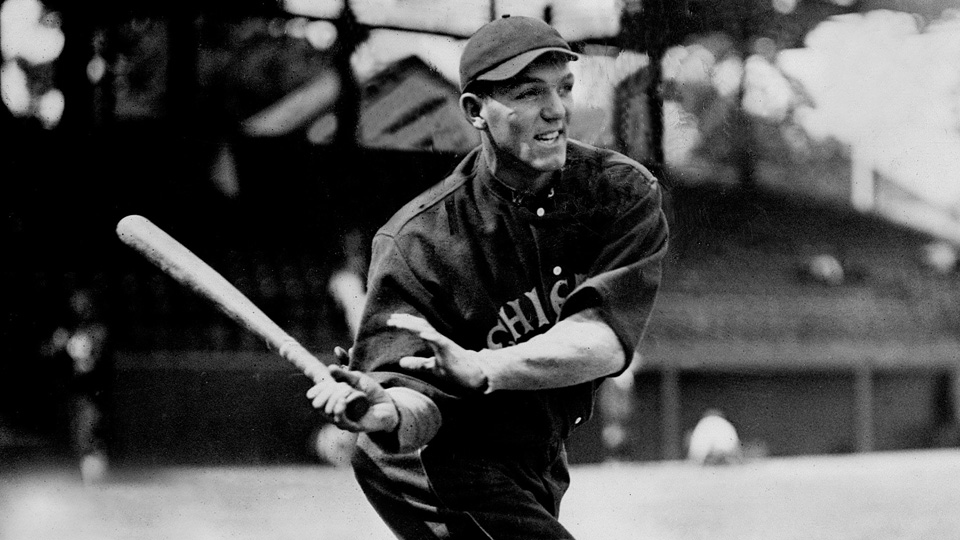

Buck Weaver was a perennial jug-eared kid, the goofy-lookin' boy who sat behind you in third grade, the one with an ubiquitous jack-o'-lantern grin.

Author Nelson Algren called him, "A joyous boy, all heart and hard-trying. A territorial animal who guarded the spiked sand around third like his life."

In many ways, Buck did what the rest of us dreamt of when we were boys on the sandlot, frustrated with our inability to master the game. He turned a base of uninspiring athletic skills into major league stardom.

When he first came up to the majors he was a below average right-handed hitter whose defense at shortstop was as raw as his batting. In his rookie season of 1912, he led the league in errors with 71, while batting only .224. About the only thing worse than his hitting and fielding was his base running, which resulted in only 13 successful steals in 33 attempts. But he was only 21, and the White Sox loved his attitude, so management was patient with him. Undiscouraged by his disappointing first term, he set about to make himself a ball player. The first step in his development was to learn to switch hit, which added nearly 50 points to his batting average in the following year. Then he practiced relentlessly to become a competent major league shortstop, and then a respected third baseman when afforded the opportunity to move over to the line. He eventually became a true star, considered one of the best third sackers in the game on both offense and defense. The progress he made was a testimony to his work ethic. He was in the major leagues for nine years. He batted just .247 over the first five, but .305 over the last four, and he seemed to be getting better every year. In his final year before the ban, when he was still in his twenties, he batted .331, just three points below Ty Cobb.

The scandal

Question #1, "Did he conspire to commit a criminal act?" can fairly be answered in the negative for all the accused, including Weaver. Question #3, "Did he actually do anything to throw the Series?" also requires a negative response in Bucky's case. He is almost universally believed to have done his best to win the 1919 Series. His manager, the team owner, the fans and the scribes all believed that he played to win and went all out on every play (possibly excepting his first at bat). If Commissioner Landis had allowed Buck to continue playing, the White Sox, or any of the other 15 teams in major league baseball, would have signed him in a heartbeat, without the slightest doubt about his unflinching will to win.

That leaves only Question 2, "Did he conspire to throw the World Series?"

The answer to that one is complicated. In his favor, Weaver never agreed to participate in the fix and he never accepted any money to do so. On the other hand, and this is a factor ignored by his apologists, he took several actions to further the conspiracy itself:

- One of the Black Sox who confessed to the grand jury, Lefty Williams, made a confession prior to his grand jury appearance in which he placed Weaver at a pre-series discussion of the fix at the Warner Hotel in Chicago between five of the Black Sox (Chick Gandil, Eddie Cicotte, Happy Felsch, Weaver and Williams), and two gamblers, identified by Williams as "Sullivan and Brown." Sullivan was later identified as "Sport" Sullivan, the famous Boston bookmaker, and Brown turned out to be Nat Evans, a trusted associate of Arnold Rothstein, the criminal mastermind who was reputed to be the financial backer of the fix. This was the first time a wide group of the players had met with those particular high-rolling gamblers. Prior to that occasion, the only player who knew Sullivan was first baseman Chick Gandil, a long-time acquaintance of the dapper gambler, dating back to Gandil's stint with the Washington Senators in 1912.

- Williams' actual grand jury testimony was even less favorable to Weaver. He revealed that immediately after the meeting described above, he, Buck Weaver and Happy Felsch had gone for a walk together, during which they discussed how to throw ball games without being detected.

- Another would-be Series fixer, "Sleepy" Bill Burns, testified in the Black Sox criminal trial that Weaver was present at a meeting at the Sinton Hotel in Cincinnati just before the opening game of the World Series, during which Burns and his associate told the players that they had lined up $100,000 to reward the players for their co-operation.

- Burns offered a more detailed account of the Sinton Hotel meeting when he was deposed for the Milwaukee civil trial in which the players sued for back wages. Burns revealed that Weaver was not only there, but was the lookout who got up once or twice to make sure there was no sign of the impeccably honest White Sox manager, Kid Gleason, in the hallway.

- In the same pre-grand-jury confession cited earlier, Lefty Williams also placed Weaver at another meeting of the conspirators, this one for players only, in Chick Gandil's room at the Sinton just before the Series opener, between the same five players who had met with Sport Sullivan at the Warner Hotel in Chicago. Williams confessed, "We asked (Gandil) when he was going to get the hundred thousand that Burns and Attell was supposed to give us. He says, 'They are supposed to give me twenty or thirty thousand after each game.'"

- Weaver freely admitted in 1922 that he had been part of a conspiracy to throw games in the 1917 season, although not as the bribed loser, but as the briber. Weaver claimed that he and many of his teammates had bought off the Detroit Tigers to throw two double headers on September 2nd and 3rd, 1917, thus assuring a pennant for the White Sox over the Red Sox. Weaver further alleged that the White Sox later reciprocated by throwing the last three games of the 1919 season to the Tigers. Those three games were meaningless to the Sox (they were up four and a half games with three to play), but were meaningful to the Tigers, who hoped to slip past the Yankees and collect the league's third place bonus money. At the time he made this admission, Weaver was attempting to demonstrate that justice was not applied equally because he had been banned for practices that were commonplace in baseball at the time, and which had been overlooked for many other players who were still in good standing.

- When Sleepy Bill Burns was deposed for the Milwaukee trial, his highly detailed testimony placed Buck Weaver at a payoff. Burns, acting as a facilitator between the players and the gamblers, took $10,000 to the players in the Sinton Hotel after game two of the series, and handed the bills to Chick Gandil. Present in that room were all of the indicted players except Joe Jackson. Two corrupt infielders, Swede Risberg and Fred McMullin, counted the money, then Gandil re-counted it in front of everyone, including Weaver.

- When baseball's most famous maverick owner, Bill Veeck, owned the White Sox many years after the scandal, he found some forgotten memorabilia deep in the bowels of Comiskey Park. Included in the treasure trove was the diary of Harry Grabiner, who had been the secretary to Charles Comiskey during the Black Sox scandal. After reviewing Grabiner's recap of an investigator's interview with Buck Weaver, Veeck wrote in "The Hustler's Handbook" (page 284): "There is very little doubt that Weaver did remain honest throughout the Series but he was hardly faced, as had been previously supposed, with a difficult last-minute decision about whether to squeal on his friends. He had months to think it over and if he had come to a calculated decision not to go along with the fix, he had also come to a calculated decision to keep his mouth shut."

- Two of Weaver's honest teammates thought he was crooked, including team captain and superstar Eddie Collins. As reported in the October 30, 1920 edition of Collyer's Eye, Collins told reporter Frank Klein that Weaver made a suspicious play in his very first at bat of the World Series: "As to the actual playing there wasn't a single doubt in my mind after I went to bat for the first time in Cincinnati. The first man up for us was Leibold. Nemo singled and when I attempted to sacrifice him I forced the lad at second. The next man up was Weaver. In the second ball pitched, Weaver gave me the "hit and run" signal and I was caught off second by the proverbial mile. When I returned to the bench, I immediately accused Weaver of not even attempting to hit the ball. I told all this to Comiskey." Regarding suspicious plays in 1920, Collins declared, "If the gamblers didn't have Weaver and Cicotte in their pocket, then I don't know a thing about baseball." Pitcher Dickie Kerr also thought that Weaver was among the players throwing games in 1920. According to Collins, as reported in Baseball Digest, June, 1949: "Dickie Kerr was pitching for us and doing well. A Boston player hit a ball that fell between Jackson and Felsch. We thought it should have been caught. The next batter bunted and Kerr made a perfect throw to Weaver for a force out. The ball pops out of Weaver's glove. When the inning was over, Kerr scaled his glove across the diamond. He looks at Weaver and Risberg who are standing together and says, 'If you'd told me you wanted to lose this game, I could have done it a lot easier.' We lose three or four more games the same way."

- The confessed ringleader of the fix, Chick Gandil, told a reporter for Sports Illustrated Magazine (September 17, 1956 issue) that Weaver had been part of a first meeting of all eight indicted White Sox the day after the Sullivan offer, and that Weaver had been an active participant. He said: "That night Cicotte and I called the other six together for a meeting and told them of Sullivan’s offer. They were all interested and thought we should reconnoiter to see if the dough would really be put on the line. Weaver suggested we get paid in advance; then if things got too hot, we could double-cross the gambler, keep the cash and also take the big end of the Series cut by beating the Reds. We agreed this was a hell of a brainy plan."

- Gandil also claimed that Weaver was an active participant in a later meeting in which the players discussed the competing offer from Sleepy Bill Burns, "Cicotte and I called a meeting of the players that night and told them about Burns. Weaver piped up, 'We might as well take his money, too, and go to hell with all of them.'"

Any of Chick Gandil's claims probably ought to be taken with many grains of salt. He is generally considered to be a scoundrel, and cannot be considered a reliable witness. Gandil either lied or misreported at least one key fact in that Sports Illustrated interview. He claimed to have dealt with Arnold Rothstein personally, which never happened, and was about as likely as a stranger being a welcome guest at J.D. Salinger's house. But even if Gandil's words are completely ignored, there is still a persuasive case that Buck Weaver was never as innocent as he always claimed to be. Lefty Williams had no reason to lie either before or during his grand jury testimony because he was under the (mistaken) impression that his co-operation would grant him immunity from punishment. Bill Burns was grilled by numerous top lawyers who tried to break his stories and failed. Moreover, every part of Burns's story was fully corroborated by his sidekick, Billy Maharg.

It seems almost certain that Buck Weaver had heard the plans to fix the series, had witnessed a payoff, and had even taken actions to further the conspiracy (acting as the lookout for a meeting he knew was illicit, and discussing the ways and means of throwing ball games). It is absolutely certain that he knew exactly what was going on. He knew before the World Series that the fix was in, and took no action to prevent his teammates from pulling it off.

If there had been a law in Illinois in 1919 against deliberately losing a public sporting event, and if therefore conspiring to throw the 1919 World Series had broken a second law, Buck Weaver would not have been guilty of the former, but would debatably have been legally guilty of the latter. His actions might be interpreted by a jury as being part of the conspiracy, or they might not, because juries are unpredictable, and might unduly weigh in such factors as the fact that Weaver played the Series honestly, even though an illegal act and the conspiracy to commit such an act should be evaluated as two completely separate crimes.

After having immersed myself in the period 1917-1924 for weeks now, having devoured every book and website I could find on the Black Sox, and having come to know them and their surrounding cast like family, I can't find it in my heart to dislike Buck Weaver or Eddie Cicotte (SEE-kott).

Of all the characters in the story, they come off as the two best human beings.

Cicotte made horrible mistakes, but had a conscience. Deep inside he was a good person who bared his soul and tried to make amends for his wrongs by living a righteous post-baseball life in virtual anonymity, with quiet dignity, working hard, keeping out of the limelight, loving his family, and sheltering his children as well as he could from the bitterness America felt toward him.

Similarly, Weaver became a quiet family man, a faithful employee to his post-Sox employers, and a great surrogate dad to his nieces when their own dad died. The movie version of "Eight Men Out" got a lot of things wrong, but it got one thing right about Bucky: he always remained a kid who loved to play baseball at the highest level. He had that taken away from him, along with his good name, but in the face of that he remained a gentle and considerate man with unending reserves of patience and optimism. Like all those who love baseball and its history, I wish that he had eventually come totally clean about his knowledge of the fix instead of making his disingenuous periodic protestations of innocence, if for no other reason than to give us a really good look behind the scenes, but I understand his loyalty, and he was loyal to a fault.

Bucky did try to take the stand in the Black Sox trial, so maybe he later offered complete co-operation and a full accounting to one or more commissioners. I don't know. But I do know this: he was beloved as a star, and remained so after his disgrace, despite remaining in the same city in which he had allowed his teammates to throw the World Series, and had thus stripped the city's team so bare of talent from the resulting expulsions that it was doomed to 40 years of mediocrity or worse. I feel that the arguments I made above may be the strongest case anyone has ever made against him - and maybe he should have blown the whistle on his teammates. Or maybe not. But I reckon if Chicago could love the guy and so completely forgive him, the rest of us can as well.

50 years after

Only a turning wind may remember

... Nelson Algren, "Ballet for Opening Day"

Next, in Part II: Shoeless Joe

Wow great article! Very interested in the Shoeless Joe one obviously. Question: you say Cicotte and Weaver were the two best human beings. Was there something more to Joe than what we've been told over the years?

ReplyDeleteThanks Scoopy for this well written opinion. I feel like I know Bucky well and he would have made a good friend. I'm looking forward to your next article about Joe.

ReplyDelete