Yes, it is true that Randy Johnson once struck out 13.41 batters per nine innings during a single season, and 10.61 per nine innings over the course of his career. Both represent the all-time records.

Yes, it is true that Nolan Ryan struck out even more batters than Johnson, 5714 to 4875, and led his league more times, 11 versus 9.

Yet I am going to propose to you that neither of those great modern pitchers was the most dominant strikeout pitcher in baseball history. In order to find the identity of that underrated fireballer, we'll have to look farther back in the baseball archives.

Why search through the past?

It's necessary because raw strikeout numbers are entirely dependent on and reflective of the era in which the pitcher's career took place. The frequency of strikeouts has varied greatly over the years, and has accelerated dramatically in the past 35 years, making it almost impossible to compare eras. According to Baseball-Reference.com's Major League Baseball Batting Encyclopedia, the number of strikeouts per nine innings has gone from 4.75 to 8.01 in just the period from 1981 until now (I'm writing this after the 2016 season), and has now increased for eleven consecutive years. In the 20th century, the number had dropped as low as 2.70. When the National League played its very first season in 1876, the number was a meager 1.13.

When I followed baseball most avidly, from the late 50s until the early 80s, a pitcher who struck out eight batters per nine innings was a real flame thrower. Tom Seaver led the NL in that category (K/9) several times with averages below eight; Jim Bunning led the AL one year with 7.1; Len Barker led the AL one year by striking out only 6.8 batters per nine innings. If a pitcher could average eight strikeouts per game in 1980, it was a truly remarkable achievement. In 2016, however, eight strikeouts per game would be below the major league average!

How, then, do we measure strikeouts in such a way that we can compare different pitchers from different eras?

I propose two measures of true dominance:

- By how much did the MLB leader beat the MLB average?

- By how much did the MLB leader beat the second-highest pitcher?

That chart is sortable, but if you're looking for the very best season, it doesn't really matter which of the two criteria you choose, because both sorting methods produce the same result: the best season of all time was Dazzy Vance's 1924, when he came close to tripling the major league average and beat the nearest competitor by an incredible 49%. Moreover, Vance's 1925 season was nearly identical - just a hair lower in each metric. Making those accomplishments even more impressive is the fact that the man who finished a distant second in 1924 was a legendary hard-throwing ace, Walter Johnson, the only man to win at least 400 games in the 20th century. That's how good the right-handed Vance was at striking batters out: more than 40% better than The Big Train.

A third Vance season (1923) is on the list as well. While Vance's 1926 and 1927 seasons are not shown in the table because he failed to beat the nearest competitor by 20% (that darned Lefty Grove), he doubled the MLB average in each of those seasons as well.

Although he is a Hall of Famer, Vance won fewer than 200 games in his career, and had no big moments to speak of. He never pitched in the post-season until he was a 43-year-old codger in his only season in St Louis, making a single unimportant middle-relief appearance for the Gas House Gang in a 10-4 loss to the Tigers in the 1934 World Series. (The 1934 Cardinals could claim the presence of a Dizzy, a Dazzy, and a Daffy in the dugout!) The Dazzler did win the National League MVP award in 1924, despite the fact that Rogers Hornsby batted a gaudy .424 that year, so you know that Vance's contemporaries realized how good he was, but his name means nothing to most modern fans and probably creates only a blurry image even to serious students of the game's history. While most of you reading this article can immediately identify photographs of Vance's mound contemporaries Lefty Grove and Walter Johnson, only those who are truly immersed in the game can pick Vance out of a line-up. I confess that I am not among that elite group, although I spend a helluva lot of time reading and writing about baseball's past.

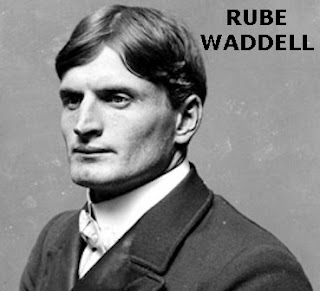

Perhaps the second most impressive appearance on the list is made by a storied eccentric lefty named Rube Waddell, a guy who occasionally made his way to the ballpark when he wasn't drinking, or chasing skirts, or leading a parade, or wrestling an alligator, or endorsing products, or acting in vaudeville, or playing with stray dogs, or chasing fire trucks. Of the seventeen seasons in baseball history which met my defined criteria, Waddell had five, yet he, like Vance, failed to reach the 200-victory level in his career. The Rube was dead at the tender age of 38, but "the candle that burns twice as bright, burns half as long." In his time he had more fun than most who live a century, and he also accomplished more than most ballplayers, if perhaps not as much as warranted by his immense talent.

Besides Vance and Waddell, only one other pitcher made the list at least three times, the great Bob Feller. I don't think I need to tell you who he was, since he led the AL in wins six times, strikeouts seven times. The right-hander finished with 266 wins, although WW2 cost him 150 starts, which would have added 80-100 wins to his total.

Nolan Ryan made only two appearances on the list, but what's astounding about his performances is that they occurred 13 years apart, yet appear almost identical by the ratios represented in the table. Over the course of a lengthy career, Ryan's appearance seemed to age normally, but his pitching remained remarkably consistent.

The Big Unit's 2001 season, when he set the record for the most strikeouts per nine innings, did appear in the table. The gigantic lefty is the most recent pitcher to make the list, and will probably be the last ever, assuming baseball's management group takes no action to curb the general rise of strikeouts, because the MLB average is now too high to double. In order to strike out twice the 2016 MLB average, a pitcher would have to amass more than sixteen Ks per nine innings.

Is sixteen possible? It does not seem so. Only one pitcher after Randy Johnson has even reached twelve in the k/9 charts, and that young man passed away less than a month ago at age 24, the victim of a tragic boating accident.

The other three men on the list, each making a single appearance, are a bit more obscure.

The memory of the Indians' Herb Score, the man picked by Ted Williams as the fastest lefty he ever faced, is bittersweet for most of us old-timers. He started his career very much like Dwight Gooden: already superlative in his rookie year (1955), absolutely dominant in year two. In Score's case there was no year three. On May 7, 1957, Score was hit in the eye by a line drive off the bat of Gil McDougald, and he never came back to glory. Surprisingly, it was not the line drive that ultimately ended his career, but elbow troubles. He started the 1958 season pitching as effectively as ever and the eye seemed to be fine, but he developed elbow problems that April and he never recovered. He struggled though a few more seasons, first with the Indians, then the White Sox, but his post-injury record in the majors was 17-26 with a 4.43 ERA. The saddest chapter of the story came in the minors. He spent his last season in pro ball with Indianapolis in AAA, where he was 0-6 with a 7.66 ERA, breaking the hearts of everyone who dreamt he would one day be the young Herb Score again.

Johnny Vander Meer finished his career with a losing record, and he made this list only because he met the criteria in a player-poor war year, but he is duly famous for another very impressive feat: in 1938, as a very young man (23), the lefty pitched two consecutive no-hitters, making him the first and still the only man in baseball history to do so. And he did that in his first full season in the bigs! Making the second game even more historic, it came in the first night game ever played in New York City. Many baseball savants thought back then that Vander Meer's potential was enormous but, like Herb Score, The Dutch Master peaked at 23 and fought his way through injuries in his remaining years. When I lived on the west coast of Florida back in the 70s and 80s, a good friend of mine was close to Vander Meer. Each of them, through independent concatenations of circumstances, had moved from Cincinnati and had eventually landed in Tampa. I never met Vander Meer, but my friend told me that the pitcher felt unjustly ignored by the Hall of Fame. If a man with a lifetime record of 119-121 felt slighted by the Hall, you can imagine how a great player like Edgar Martinez must feel.

Left-handed Cy Seymour is the last name on the list and in some ways the most interesting. Seymour was the strikeout king in 1897-1899, but went on to a great major league career as an outfielder!

In order to tell his story, I'm just going to quote from his SABR bio: "If a young, successful major league pitcher had decided to become an outfielder in 2001, it would have been news. And if he had hit above .300 for the next five straight years, culminating in 2005 by winning the league's batting crown with a .377 average, he would have graced magazine covers. Finally, if upon his retirement in 2010, he had accumulated 1700 hits and generated a lifetime batting average of .303 to go along with his sixty-plus pitching victories, writers would be salivating at the opportunity to elect him to the Hall of Fame. A century ago there was just a player who collected 1723 hits and became a lifetime .303 hitter after winning 61 games as a major league pitcher. His name was James Bentley 'Cy' Seymour, perhaps the greatest forgotten name of baseball."

No comments:

Post a Comment